I started working at a company named Arvin in 1994. It no longer exists. In 2000, they had a “merger of equals” with a company named Meritor. They promised the Arvin shareholders that, in 2 years, the CEO of Arvin, Bill Hunt, would become the CEO of the combined ArvinMeritor. The execs split $50M in bonuses, $15M of which went to Hunt. As soon as the ink was dry, Meritor started liquidating Arvin’s divisions, and Arvin VP’s started pulling the rip cords on their golden parachutes. One year into the deal, the board pulled the $19M ripcord on Hunt’s golden parachute for him. In just another 2 years, all that was left of Arvin was the OEM exhaust division (Arvin’s largest), which they renamed EmCon, and then sold to a private equity firm. Then they changed their name back to Meritor, and probably had a drink and played golf.

Textbook corporate raidership. And the senior leadership of Arvin all “got theirs.”

From 2000 to 2003, there was a game of musical chairs played internally for who would be doing what in the “merged” company. I had been working in the engineering group, as a programmer and system admin. The project I was working on was determined to be redundant, and was canceled. (A very long story, which picks back up at the end, but one for another day.)

I quickly found a spot in the IT group, and moved over to doing systems administration proper. As things started to shake out, one of Meritor’s “brilliant” corporate leadership moves was to get everyone to read the book, Who Moved My Cheese. The Wikipedia page summarizes it well:

Who Moved My Cheese? An Amazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and in Your Life, published on September 8, 1998, is a motivational business fable. The text describes change in one’s work and life, and four typical reactions to those changes by two mice and two “Littlepeople”, during their hunt for cheese. A New York Times business bestseller upon release, Who Moved My Cheese? remained on the list for almost five years and spent over 200 weeks on Publishers Weekly’s hardcover nonfiction list. It has sold more than 26 million copies worldwide in 37 languages and remains one of the best-selling business books.

In a move that surprised not even myself, I was the first one in my group to be handed the communal copy by my boss. I knew that I could be difficult, so even I thought it was appropriate to start with me. What I should have seen coming, though, was that I was about to get the shaft, and thus, according to management’s plans, I needed it first.

In a few short months, I had setup and configured a Sun E10000 from scratch, by the book, with all the bells and whistles, configured 10 TB of EMC disk cabinets, setup a backup area network and a 384-tape silo and all the backups, and gotten several other mission-critical machines up and running. Just about the time it was all done and running like a sewing machine, with lots of housekeeping scripts setup to automate and groom the operation, I was told I would have to hand it all over to the Windows admin, and switch over to doing Windows administration.

Uh, wut?

Just prior to this, I was also told that I would be taken off the bonus plan, with nothing given in return. Still stinging from this, I was aghast and offended. I pulled a string, called in a favor, and got moved back to engineering. This was a mistake, from both ends.

I hung my decision on one thing: we had bought a $50,000 PC server to be the backbone of managing our 150-or-so Windows servers, then chickened out of spending the $250,000 it would have taken to buy the management software the machine was intended to run. Because of this, this massive machine was just sitting around collecting dust. In fact, we used it on several occasions to host the game servers on LAN party nights. Anyway, since it seemed like we needed this really huge, expensive piece of software to manage the Windows “farm,” the job seemed intimidating without it, so I didn’t want to do it.

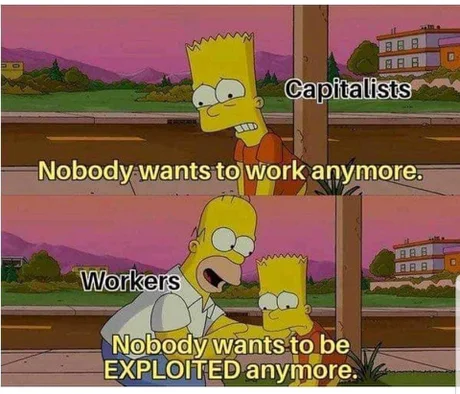

This was precisely what the book was supposed to get me to see past. I should have recognized the opportunity for what it was, and made the best of it. I should have made those Windows servers my puppets. If they wouldn’t buy the management software, I should have written my own automation, like I did for the Sun machines. But, no, I didn’t want to be seen as working with Windows — yuck! — I was a Linux Man! I also didn’t get along well, personally, with my boss, and it seemed like I wasn’t getting any credit for the work I had already done with the Sun equipment. As per the graphic above, I felt exploited.

So I abandoned the group, and was soon put on a project which became a living nightmare. For 3 years, I worked for absolute narcissist who I watched lie to senior management to try to build an internal empire, and achieve his career goals, and who relentlessly ridiculed me for a perceived professional slight by someone form whom I had worked for previously.

I look back and wonder. If I had swallowed my pride, and made the Windows servers dance to my tune, where would I be today? If I hadn’t stayed a Linux Man, would I have learnt the world of Gentoo? Would I have wound up at AEI and DataCave? Would I have eventually worked my way into programming bliss with Rails? Would I have returned to writing engineering apps for engineers again? Maybe; maybe not. I love what I do these days, and hope to do it till I retire. So I guess it doesn’t matter how I got here.